Listening to Reggie is like trying to watch TV with a busted aerial. You can't quite make out what's going on...It just seem like random words coming from multiple voices and then there's a moment of clarity, You get it finally...And then it's gone again...

YouTube Comment from ISureDoLikeCats

It’s easy to forget that people only began watching videos on YouTube in 2005, downloading songs off the iTunes store in 2003, and hearing music in MP3 format back in 1993. If you were a musician in the decades preceding the ‘90s and wanted to create a film seen by millions of people, your movie better be named Purple Rain or A Hard Day’s Night, with a serious studio supporting its release.

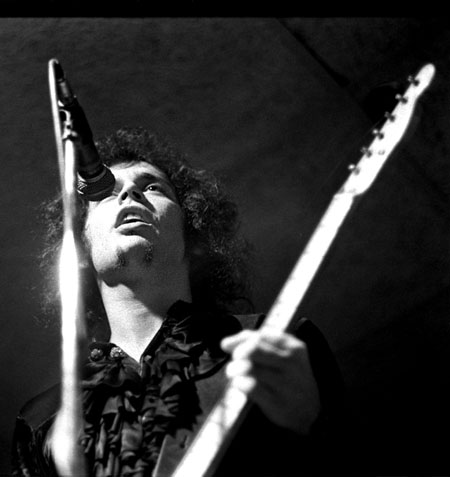

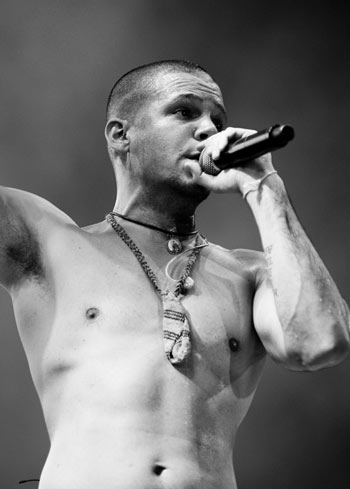

Musician, comedian, and actor Reggie Watts couldn’t have existed 15 years ago, for the same reason Daft Punk couldn’t have existed before the invention of the synthesizer. Technology enables Watts to create, perform, and distribute his art. This multimedia output illustrates how Reggie represents the future of music, one where artists possess a liberating and terrifying amount of control over their work.

Watts puts out comedy videos on his YouTube channel, Jash. He uses an unconventional array of equipment in creating his mind-boggling, improvised live shows. The guy basically does whatever the fuck he wants. That’s only possible because the tools to film, record, and publish have never been cheaper or more accessible.

This ease of creative access scares a lot of people. New Republic critic William Giraldi writes, “When everyone’s an artist and no one spends money on art, art is stripped of any economic transaction and serious artists can’t earn a living.” In other words, if anyone can do what Watts does, what makes Watts particularly special?

That’s a shortsighted view. It doesn’t take into account how art and its methods of creation are changing faster than ever before. People said that recorded music would kill live performance. Composer John Philip Sousa, the 20th century marching band composer, stated that singers “would not have a vocal cord left.” In case you never go outside, you may be happy to hear this hasn’t happened yet.

If Watts is special, it isn’t due to his ability to stand out from a crowded field of musicians. Instead, it’s the way he adapts and incorporates advances in the ways people make music. Reggie’s talent rests in an ability to make something creative out of the exact technologies people worry will kill creativity.

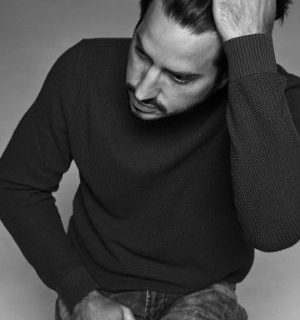

What may be frightening folks about Watts and similar tech-savvy artists is how they hearken that music will become unrecognizable in the next 15 years. Electronic musician Dan Deacon puts it succinctly, saying that just like “there was a time before photography, [and] there was a time before film,” we currently live in a time in which a new form of music is evolving from our present cultural conditions.

It’s impossible to make predictions about what that musical mutation will look like. Maybe it will meld live performances with virtual reality, allowing digital spectators to take in a concert from the lens of an Oculus Rift. Perhaps it will be a symphony for the senses, integrating tactile feedback synchronized to the rhythms of a song. The one certainty is that these musical frontiers will be similar to the work of Reggie Watts––brilliant, baffling, and disorienting.