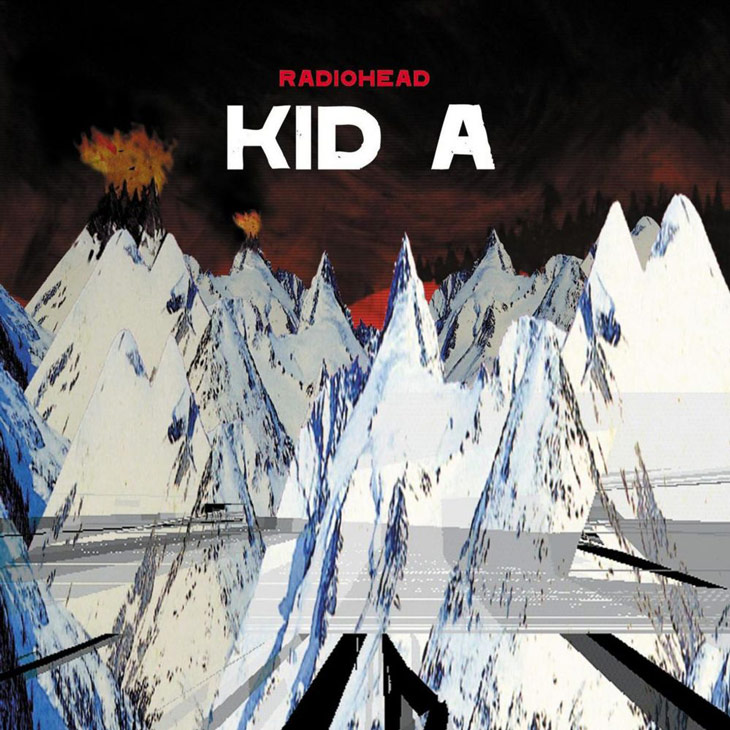

Radiohead - Kid A

Radiohead - Kid A

“There are two colors in my head”

Let’s get this out of the way: Kid A is one of my favorite albums ever. “Everything in its Right Place” is a movie played in slow motion over the events of my adult life. “Kid A” is my youth, meandering and childlike; “The National Anthem” is my anger; “How to Disappear Completely” is my abyss; “Treefingers” is everything I am not; “Optimistic” is my battle and “In Limbo” feels like the fractals that separate reality lost in the rain. “Idioteque” is terror at its most abjectly rhythmic; “Morning Bell” is my final march, and “Motion Picture Soundtrack” is my aspirations laid bare.

The album slides gracefully from moments akin to Schoenberg’s “Ondes Martenot” to crushing bass, guitar lines like heart monitors, and Thom Yorke’s lilting loneliness. At moments, it feels like Stravinsky playing Aphex Twin records in his mother’s basement to get inspiration for Rite of Spring. This is the kind of unreal that arouses my devotion in the most meaningful ways.

The album flows beautifully from track to track in an ether of death and despair, with moments of uplift squashed by moments of silence. Grandiosity falls to the wayside underneath chaotic horn sections, and jazz drums become drum machines become nothing at all. Kid A is in a state of perpetual decay, ecstasy, and, ultimately despair—a sine wave on the move.

And the fanboys almost killed it for me. For so long, I hated this record.

I hear five musicians bored with the standard guitar, bass, and drum combination fucking around to see what sticks, and having a good time along the way.

Loving a record is not wrong. We all have those cuts that we go to again and again, time after time, for whatever reason. Defending art you love is justifiable. But with this record, the love is weaponized. The arguments of its merits—knowing which jazz, electronic and classical composers—influence it. Everything about these arguments is meant to dominate, entitle, and make the person loving the record valuable.

But when I hear this record, I don’t hear those influences that hit like a dart across a musical underground board. I hear five musicians bored with the standard guitar, bass, and drum combination fucking around to see what sticks, and having a good time along the way. It’s honest, fluid, and beautiful. Eventually, I divested myself of enough pride to let myself stop hating and fall in love.

But I only fell in love by being wrong; which, at the end of the day, I must prefer over being right.

Until everything is in its right place.